Let us introduce our country

A few words about IRAN

IRAN UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES :

Iran, formally known as Persia before 1935, is home to 26 UNESCO World Heritage Sites and 61 additional historic sites on the UNESCO tentative list.

ANCIENT HISTORY AND BIRTHPLACE OF THE FIRST EMPIRE

Iran is an ancient land with an even more ancient civilization and the starting point of many inventions, which have helped shape human society throughout history. Excavations of different sites in western Iran have shed light on the Middle Stone Age period, suggesting that this was where the domestication of animals and plants began. Urban settlements in Iran date back to 4,000 BC, and the Iranian civilization predates the Egyptian one by 500 years, the Indian one by 1,000 years, the Chinese one by 2,000 years, the Greek one by 3,000 years, and the Roman one by 4,000 years.

Explore Iran’s 26 UNESCO World Heritage Sites as a point of inspiration for your next cultural adventure:

The Armenian Monastic Ensembles of Iran – East Azerbaijan

The Armenian Monastic Ensembles of Iran, in the northwest of the country, consists of three monastic ensembles of the Armenian Christian faith: St Thaddeus and St Stepanos and the Chapel of Dzordzor. These edifices – the oldest of which, St Thaddeus, dates back to the 7th century – are examples of the outstanding universal value of the Armenian architectural and decorative traditions. They testify to critical interchanges with the other regional cultures, particularly the Byzantine, Orthodox, and Persian. Situated on the south-eastern fringe of the central zone of the Armenian cultural space, the monasteries constituted a major center for disseminating that culture in the region. They are the last regional remains of this culture that are still in a satisfactory state of integrity and authenticity. Furthermore, as places of pilgrimage, the monastic ensembles are living witnesses of Armenian religious traditions through the centuries.

Bam and its Cultural Landscape – (Arg-e Bam) / Kerman Province

Bam is situated in a desert environment on the southern edge of the Iranian high plateau. The origins of Bam can be traced back to the Achaemenid period (6th to 4th centuries BC). Its heyday was from the 7th to 11th centuries, being at the crossroads of important trade routes and known for producing silk and cotton garments. The existence of life in the oasis was based on the underground irrigation canals, the qanāts, of which Bam has preserved some of the earliest evidence in Iran. Arg-e Bam is the most representative example of a fortified medieval town built in vernacular technique using mud layers (Chineh ).

Bisotun – Kermanshah Province

Bisotun is located along the ancient trade route linking the Iranian high plateau with Mesopotamia and features remains from the prehistoric times to the Median, Achaemenid, Sassanian, and Ilkhanid periods. The principal monument of this archaeological site is the bas-relief and cuneiform inscription ordered by Darius I, The Great when he rose to the throne of the Persian Empire in 521 BC. The bas-relief portrays Darius holding a bow as a sign of sovereignty and treading on the chest of a figure who lies on his back before him. According to legend, the figure represents Gaumata, the Median Magus and pretender to the throne whose assassination led to Darius’s rise to power. Below and around the bas-reliefs, there are ca. 1,200 lines of inscriptions telling the story of the battles Darius waged in 521-520 BC against the governors who attempted to take apart the Empire founded by Cyrus. The inscription is written in three languages. The oldest is an Elamite text referring to legends describing the king and the rebellions. This is followed by a Babylonian version of similar legends. The last phase of the inscription is significant, as it is here that Darius introduced the Old Persian version of his res gestae (things done). This is the only known monumental text of the Achaemenids to document Darius I’s re-establishment of the Empire. It also bears witness to the interchange of influences in the development of monumental art and writing in the region of the Persian Empire. There are also remains from the Median period (8th to 7th centuries B.C.) and the Achaemenid (6th to 4th centuries B.C.) and post-Achaemenid periods.

Cultural Landscape of Hawraman/Uramanat – Kermanshah Province

The remote and mountainous landscape of Hawraman/Uramanat bears testimony to the traditional culture of the Hawrami people, an agropastoral Kurdish tribe that has inhabited the region since about 3000 BCE. At the heart of the Zagros Mountains in Kurdistan and Kermanshah along the western border of Iran, the property encompasses two components: the Central-Eastern Valley (Zhaverud and Takht, in Kurdistan Province); and the Western Valley (Lahun, in Kermanshah Province). The mode of human habitation in these two valleys has been adapted over millennia to the rough mountainous environment. Tiered steep-slope planning and architecture, gardening on dry-stone terraces, livestock breeding, and seasonal vertical migration are among the distinctive features of the local culture and life of the semi-nomadic Hawrami people who dwell in lowlands and highlands during different seasons of each year. Their uninterrupted presence in the landscape is also characterized by exceptional biodiversity and endemism, as evidenced by stone tools, caves and rock shelters, mounds, remnants of permanent and temporary settlement sites, workshops, cemeteries, roads, villages, castles, and more. The 12 villages included in the property illustrate the Hawrami people’s evolving responses to the scarcity of productive land in their mountainous environment through the millennia.

Cultural Landscape of Maymand – Kerman Province

Maymand is a self-contained, semi-arid area at the end of a valley at the southern extremity of Iran’s central mountains. The villagers are semi-nomadic agro-pastoralists. They raise their animals on mountain pastures, living in temporary settlements in spring and autumn. They live lower down the valley in the winter months in cave dwellings carved out of the soft rock (kamar), an unusual form of housing in a dry, desert environment. This cultural landscape is an example of a system that appears to have been more widespread in the past and involves the movement of people rather than animals.

Golestan Palace – Tehran

The lavish Golestan Palace is a masterpiece of the Qajar era, embodying the successful integration of earlier Persian crafts and architecture with Western influences. The walled Palace, one of the oldest groups of buildings in Teheran, became the seat of government of the Qajar family, which came into power in 1779 and made Teheran the country’s capital—built around a garden featuring pools as well as planted areas, the palace’s most characteristic features and rich ornaments date from the 19th century. It became a center of Qajari arts and architecture. It is an outstanding example and has remained a source of inspiration for Iranian artists and architects. It represents a new style incorporating traditional Persian arts and crafts and elements of 18th-century architecture and technology.

Gonbad-e Qābus – Golestan Province

The 53 m high tomb built-in ad 1006 for Qābus Ibn Voshmgir, Ziyarid ruler and literati, near the ruins of the ancient city of Jorjan in north-east Iran, bears testimony to the cultural exchange between Central Asian nomads and the ancient civilization of Iran. The tower is the only remaining evidence of Jorjan, a former center of arts and science destroyed during the Mongols’ invasion in the 14th and 15th centuries. It is an outstanding and technologically innovative example of Islamic architecture that influenced sacral buildings in Iran, Anatolia, and Central Asia. Built of unglazed fired bricks, the monument’s intricate geometric forms constitute a tapering cylinder with a diameter of 17–15.5 m, topped by a conical brick roof. It illustrates the development of mathematics and science in the Muslim world at the turn of the first millennium AD.

Historic City of Yazd – Yazd Province

The City of Yazd is located in the middle of the Iranian plateau, 270 km southeast of Isfahan, close to the Spice and Silk Roads. It bears living testimony to using limited resources for survival in the desert. Water is supplied to the city through a qanat system developed to draw underground water. The earthen architecture of Yazd has escaped the modernization that destroyed many traditional earthen towns, retaining its traditional districts, the qanat system, traditional houses, bazaars, hammams, mosques, synagogues, Zoroastrian temples, and the historic garden of Dolat-Abad.

The City of Yazd is located in the deserts of Iran, close to the Spice and Silk Roads. It is a living testimony to the intelligent use of limited available resources in the desert for survival. Water is brought to the city by the qanat system. Each city district is built on a qanat and has a communal center. Buildings are constructed of earth. The use of soil in buildings includes walls and roofs by constructing vaults and domes. Houses are built with courtyards below ground level, serving underground areas. Wind-catchers, yards, and thick earthen walls create a pleasant microclimate. Partially covered alleyways together with streets, public squares, and courtyards contribute to a lovely urban quality. The city escaped the modernization trends that destroyed many traditional earthen towns. Today, it survives with its traditional districts, the qanat system, traditional houses, bazaars, hammams, water cisterns, mosques, synagogues, Zoroastrian temples, and the historic garden of Dolat-Abad. The city enjoys the peaceful coexistence of three religions: Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism.

Masjed-e Jāmé of Isfahan – Isfahan Province

Located in the historic center of Isfahan, the Masjed-e Jāmé (‘Friday mosque’) can be seen as a stunning illustration of the evolution of mosque architecture over twelve centuries, starting in ad 841. It is the oldest preserved edifice in Iran and a prototype for later mosque designs throughout Central Asia. The complex, covering more than 20,000 m2, is also the first Islamic building that adapted the four courtyard layout of Sassanid palaces to Islamic religious architecture. Its double-shelled ribbed domes represent an architectural innovation that inspired builders throughout the region. The site also features remarkable decorative details representative of stylistic developments over more than a thousand years of Islamic art.

The City of Yazd is located in the deserts of Iran, close to the Spice and Silk Roads. It is a living testimony to the intelligent use of limited available resources in the desert for survival. Water is brought to the city by the qanat system. Each city district is built on a qanat and has a communal center. Buildings are constructed of earth. The use of soil in buildings includes walls and roofs by constructing vaults and domes. Houses are built with courtyards below ground level, serving underground areas. Wind-catchers, yards, and thick earthen walls create a pleasant microclimate. Partially covered alleyways together with streets, public squares, and courtyards contribute to a lovely urban quality. The city escaped the modernization trends that destroyed many traditional earthen towns. Today, it survives with its traditional districts, the qanat system, traditional houses, bazaars, hammams, water cisterns, mosques, synagogues, Zoroastrian temples, and the historic garden of Dolat-Abad. The city enjoys the peaceful coexistence of three religions: Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism.

Meidan Emam or Naghsh-e Jahan Square – Esfahan Province

Built by Shah Abbas I the Great at the beginning of the 17th century and bordered on all sides by monumental buildings linked by a series of two-storeyed arcades, the site is known for the Royal Mosque, the Mosque of Sheykh Lotfollah, the magnificent Portico of Qaysariyyeh and the 15th-century Timurid palace. They are an impressive testimony to the level of social and cultural life in Persia during the Safavid era.

The Meidan Emam is a public urban square in the center of Esfahan, a city located on the main north-south and east-west routes crossing central Iran. It is one of the largest city squares in the world and an outstanding example of Iranian and Islamic architecture. Built by the Safavid Shah Abbas I in the early 17th century, the square is bordered by two-story arcades and anchored on each side by four magnificent buildings: to the east, the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque; to the west, the pavilion of Ali Qapu; to the north, the entrance of Qeyssariyeh; and to the south, the celebrated Royal Mosque. A homogenous urban ensemble built according to a unique, coherent, and harmonious plan, the Meidan Emam was the heart of the Safavid capital and is an exceptional urban realization.

Also known as Naghsh-e Jahan (“Image of the World”) and formerly as Meidan-e Shah, Meidan Emam is not typical of urban ensembles in Iran, where cities are usually tightly laid out without sizeable open spaces.

Pasargadae – Fars Province

Pasargadae was the first dynastic capital of the Achaemenid Empire, founded by Cyrus II the Great in Pars, the homeland of the Persians, in the 6th century BC. Its palaces, gardens, and the mausoleum of Cyrus are outstanding examples of the first phase of royal Achaemenid art and architecture and exceptional testimonies of Persian civilization. Particularly noteworthy vestiges in the 160-ha site include the Mausoleum of Cyrus II; Tall-e Takht, a fortified terrace; and a royal ensemble of gatehouse, audience hall, residential palace, and gardens. Pasargadae was the capital of the first great multicultural Empire in Western Asia. Spanning the Eastern Mediterranean and Egypt to the Hindus River, it is considered the first Empire that respected the cultural diversity of its different peoples. This was reflected in Achaemenid architecture, a synthetic representation of other cultures.

Founded in the 6th century BC in the heartland of the Persians (today the province of Fars in southwestern Iran), Pasargadae was the earliest capital of the Achaemenid (First Persian) Empire. The city was created by Cyrus the Great with contributions from the different peoples who comprised the first great multicultural Empire in Western Asia. The archaeological remains of its palaces and garden layout and the tomb of Cyrus constitute an outstanding example of the first phase of the evolution of royal Achaemenid art and architecture and exceptional testimony to the Achaemenid civilization in Persia. The “Four Gardens” type of royal ensemble, created in Pasargadae, became a prototype for Western Asian architecture and design.

Pasargadae stands as an exceptional witness to the Achaemenid civilization. The vast Achaemenid Empire, which extended from the eastern Mediterranean and Egypt to the Hindus River in India, is considered the first Empire to be characterized by a respect for the cultural diversity of its peoples. This respect was reflected in the royal Achaemenid architecture, which became a synthesized representation of the Empire’s different cultures. Pasargadae represents the first phase of this development, specifically Persian architecture, which later found its full expression in the city of Persepolis.

Persepolis – Fars Province

Founded by Darius I in 518 B.C., Persepolis was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire. It was built on an immense half-artificial, half-natural terrace, where the king of kings created an impressive palace complex inspired by Mesopotamian models. The importance and quality of the monumental ruins make it a unique archaeological site.

Persepolis, whose magnificent ruins rest at the foot of Kuh-e Rahmat (Mountain of Mercy) in southwestern Iran, is the world’s greatest archaeological site. Renowned as the gem of Achaemenid (Persian) ensembles in architecture, urban planning, construction technology, and art, the royal city of Persepolis ranks among the archaeological sites that have no equivalent and which bear unique witness to a most ancient civilization. The city’s immense terrace was begun about 518 BCE by Darius the Great, the Achaemenid Empire’s king. On this terrace, successive kings erected a series of architecturally stunning palatial buildings, including the massive Apadana palace and the Throne Hall (“Hundred-Column Hall”).

Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of Fars Region – Fars Province

The eight archaeological sites are located in the southeast of Fars Province: Firuzabad, Bishapur, and Sarvestan. The fortified structures, palaces, and city plans date back to the earliest and latest times of the Sassanian Empire, which stretched across the region from 224 to 658 CE. Among these sites are the capital built by the founder of the dynasty, Ardashir Papakan, and the city and architectural structures of his successor, Shapur I. The archaeological landscape reflects the optimized utilization of natural topography. It bears witness to the influence of Achaemenid and Parthian cultural traditions and Roman art, which had a significant impact on the architecture of the Islamic era.

The serial property Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of the Fars Region comprises eight selected archaeological site components in three geographical area contexts at Firuzabad, Bishapur, and Sarvestan, all located in the Fars Province of southern Iran. The components include fortification structures, palaces, reliefs and city remains dating back to the earliest and latest moments of the Sassanid Empire, which stretched across the region from 224 to 651 CE. Among the sites is the dynasty founder Ardashir Papakan’s military headquarters and first capital and the city and architectural structures of his successor, the ruler Shapur I. In Sarvestan, a monument dating into the Early Islamic period illustrates the transition from the Sassanid to the Islamic era.

Shahr-i Sokhta – Sistan and Baluchestan Province

Shahr-i Sokhta, meaning ‘Burnt City’, is located at the junction of Bronze Age trade routes crossing the Iranian plateau. The remains of the mud-brick city represent the emergence of the first complex societies in eastern Iran. Founded around 3200 BC, it was populated during four main periods up to 1800 BC. During that time, there developed several distinct areas within the city: those where monuments were built and separate quarters for housing, burial, and manufacture. Diversions in watercourses and climate change led to the eventual abandonment of the city in the early second millennium. The structures, burial grounds, and many significant artifacts unearthed there, and their well-preserved state due to the desert climate, make this site a rich source of information regarding the emergence of complex societies and contacts between them in the third millennium BC.

Located at the junction of Bronze Age trade routes crossing the Iranian plateau, the remains of the mud-brick city of Shahr-i Sokhta bear witness to the emergence of the first complex societies in eastern Iran. Founded around 3200 BCE, the city was populated during four main periods up to 1800 BCE, during which time there developed several distinct areas in the town. These include a monumental area, residential areas, industrial zones, and a graveyard.

Sheikh Safi al-din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble in Ardabil

Built between the beginning of the 16th century and the end of the 18th century, this place of spiritual retreat in the Sufi tradition uses Iranian traditional architectural forms to maximize the use of available space to accommodate a variety of functions (including a library, a mosque, a school, mausolea, a cistern, a hospital, kitchens, a bakery, and some offices). It incorporates a route to reach the shrine of the Sheikh divided into seven segments, which mirror the seven stages of Sufi mysticism, separated by eight gates, which represent the eight attitudes of Sufism. The ensemble includes well-preserved and richly ornamented facades and interiors with a remarkable collection of antique artifacts. It constitutes a rare ensemble of elements of medieval Islamic architecture.

Sheikh Safi al-Din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble were built as a small microcosmic city with bazaars, public baths, squares, religious buildings, houses, and offices. It was the largest and most complete khānegāh and the most prominent Sufi shrine since it hosts the tomb of the founder of the Safavid Dynasty. For these reasons, it has evolved into a display of sacred works of art and architecture from the 14th to the 18th century and a center of Sufi religious pilgrimage.

Located at the junction of Bronze Age trade routes crossing the Iranian plateau, the remains of the mud-brick city of Shahr-i Sokhta bear witness to the emergence of the first complex societies in eastern Iran. Founded around 3200 BCE, the city was populated during four main periods up to 1800 BCE, during which time there developed several distinct areas in the town. These include a monumental area, residential areas, industrial zones, and a graveyard.

Shushtar Historical Hydraulic System – Khuzestan Province

Shushtar, Historical Hydraulic System, inscribed as a masterpiece of creative genius, can be traced back to Darius the Great in the 5th century B.C. It involved the creation of two main diversion canals on the river Kârun, one of which, the Gargar canal, is still in use providing water to the city of Shushtar via a series of tunnels that supply water to mills. It forms a spectacular cliff from which water cascades into a downstream basin. It then enters the plain situated south of the city, where it has enabled the planting of orchards and farming over an area of 40,000 ha—known as Mianâb (Paradise). The property has an ensemble of great sites, including the Salâsel Castel, the operation center of the entire hydraulic system, the tower where the water level is measured, damns, bridges, basins, and mills. It bears witness to the know-how of the Elamites and Mesopotamians and more recent Nabatean expertise and Roman building influence.

Soltaniyeh – Zanjan Province

The mausoleum of Oljaytu was constructed in 1302–12 in the city of Soltaniyeh, the capital of the Ilkhanid dynasty, which the Mongols founded. Situated in the province of Zanjan, Soltaniyeh is one of the outstanding examples of the achievements of Persian architecture and a key monument in the development of its Islamic architecture. The octagonal building is crowned with a 50 m tall dome covered in turquoise-blue faience and surrounded by eight slender minarets. It is the earliest existing example of the double-shelled dome in Iran. The mausoleum’s interior decoration is also outstanding, and scholars such as A.U. Pope has described the building as ‘anticipating the Taj Mahal.’

In northwestern Iran’s city of Soltaniyeh, briefly, the capital of Persia’s Ilkhanid dynasty (a branch of the Mongol dynasty) during the 14th century, stands the Mausoleum of Oljaytu, its stunning dome covered with turquoise-blue faience tiles. Constructed in 1302-12, the tomb of the eighth Ilkhanid ruler is the main feature remaining from the ancient city; today, it dominates a rural settlement surrounded by the fertile pasture of Soltaniyeh. The Mausoleum of Oljaytu is recognized as the architectural masterpiece of its period and an outstanding achievement in the development of Persian architecture, particularly in its innovative double-shelled dome and interior decoration

The Mausoleum of Oljaytu is an essential link and critical monument in the development of Islamic architecture in central and western Asia.

Susa – Khuzestan Province

Located in the southwest of Iran, in the lower Zagros Mountains, the property encompasses a group of archaeological mounds rising on the eastern side of the Shavur River and Ardeshir’s palace on the opposite bank of the river. The excavated architectural monuments include administrative, residential, and palatial structures. Susa contains several layers of superimposed urban settlements in a continuous succession from the late 5th millennium BCE until the 13th century CE. The site bears exceptional testimony to the Elamite, Persian, and Parthian cultural traditions, largely disappearing.

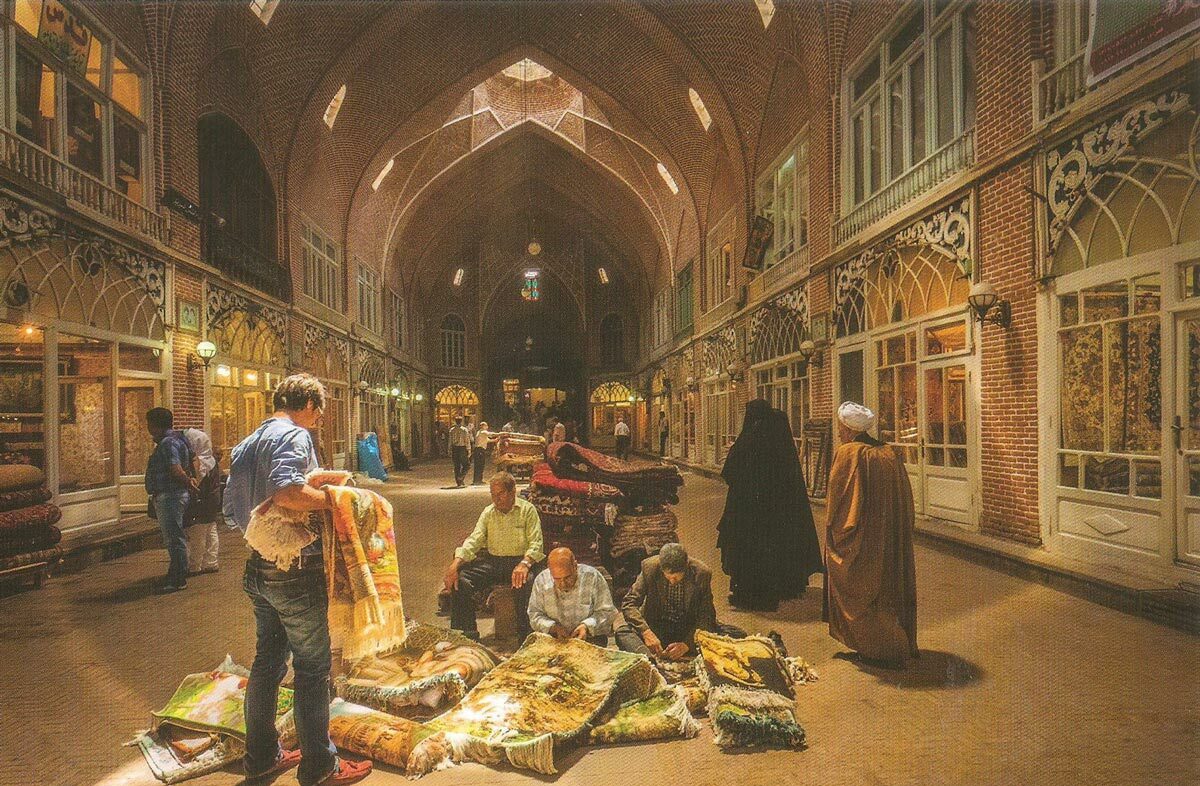

Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex – East Azerbaijan Province

Tabriz has been a place of cultural exchange since antiquity, and its historic bazaar complex is one of the most important commercial centers on the Silk Road. Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex consists of a series of interconnected, covered brick structures, buildings, and enclosed spaces for different functions. Tabriz and its Bazaar were already prosperous and famous in the 13th century when the town in the province of Eastern Azerbaijan became the capital city of the Safavid kingdom. The city lost its status as capital in the 16th century but remained important as a commercial hub until the end of the 18th century, expanding Ottoman power. It is one of the complete examples of Iran’s traditional commercial and cultural system.

Tabriz Historic Bazaar bears witness to one of the most complete socio-cultural and commercial complexes among bazaars. It has developed over the centuries into an exceptional physical, economic, social, political, and religious complex in which specialized architectural structures, functions, professions, and people from different cultures are integrated into a unique living environment. The lasting role of the Tabriz Bazaar is reflected in the layout of its fabric and in the highly diversified and reciprocally integrated architectural buildings and spaces, which have been a prototype for Persian urban planning.

Takht-e Soleyman – East Azerbaijan Province

The archaeological site of Takht-e Soleyman, in northwestern Iran, is situated in a valley set in a volcanic mountain region. The site includes the principal Zoroastrian sanctuary partly rebuilt in the Ilkhanid (Mongol) period (13th century) as well as a temple of the Sasanian period (6th and 7th centuries) dedicated to Anahita. The site has important symbolic significance. The designs of the fire temple, the palace, and the general layout have strongly influenced the development of Islamic architecture.

The archaeological ensemble Takht-e Soleyman (“Throne of Solomon”) is situated on a remote plain surrounded by mountains in northwestern Iran’s West Azerbaijan province. The site has vital symbolic and spiritual significance related to fire and water – the principal reason for its occupation from ancient times – and stands as an exceptional testimony of the continuation of a cult associated with fire and water for some 2,500 years. In a harmonious composition inspired by its natural setting, the remains of an exceptional ensemble of royal architecture of Persia’s Sasanian dynasty (3rd to 7th centuries) are located here. Integrated with the palatial architecture is an outstanding example of a Zoroastrian sanctuary; this composition at Takht-e Soleyman can be considered an important prototype.

Tchogha Zanbil – Khuzestan Province

The ruins of the holy city of the Kingdom of Elam, surrounded by three massive concentric walls, are found at Tchogha Zanbil. Founded c. 1250 B.C., the city remained unfinished after it was invaded by Ashurbanipal, as shown by the thousands of unused bricks left at the site.

Located in ancient Elam (today Khuzestan province in southwest Iran), Tchogha Zanbil (Dur-Untash, or City of Untash, in Elamite) was founded by the Elamite king Untash-Napirisha (1275-1240 BCE) as the religious center of Elam. The principal element of this complex is an enormous ziggurat dedicated to the Elamite divinities Inshushinak and Napirisha. It is the most immense ziggurat outside of Mesopotamia and the best preserved of this type of stepped pyramidal monument. The archaeological site of Tchogha Zanbil is a unique expression of the culture, beliefs, and ritual traditions of one of the oldest indigenous peoples of Iran. Our knowledge of the architectural development of the middle Elamite period (1400-1100 BCE) comes from the ruins of Tchogha Zanbil and of the capital city of Susa 38 km to the northwest of the temple).

The archaeological site of Tchogha Zanbil covers a vast, arid plateau overlooking the rich valley of the river Ab-e Diz and its forests. A “sacred city” for the king’s residence, it was never completed, and only a few priests lived there until it was destroyed by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal about 640 BCE. The complex was protected by three concentric enclosure walls:

An outer wall about 4 km in circumference encloses a vast complex of residences and the royal quarter, where three monumental palaces have been unearthed (one is considered a tomb-palace that covers the remains of underground baked-brick structures containing the burials of the royal family).

A second wall was protecting the temples (Temenus).

The innermost wall encloses the focal point of the ensemble, the ziggurat.

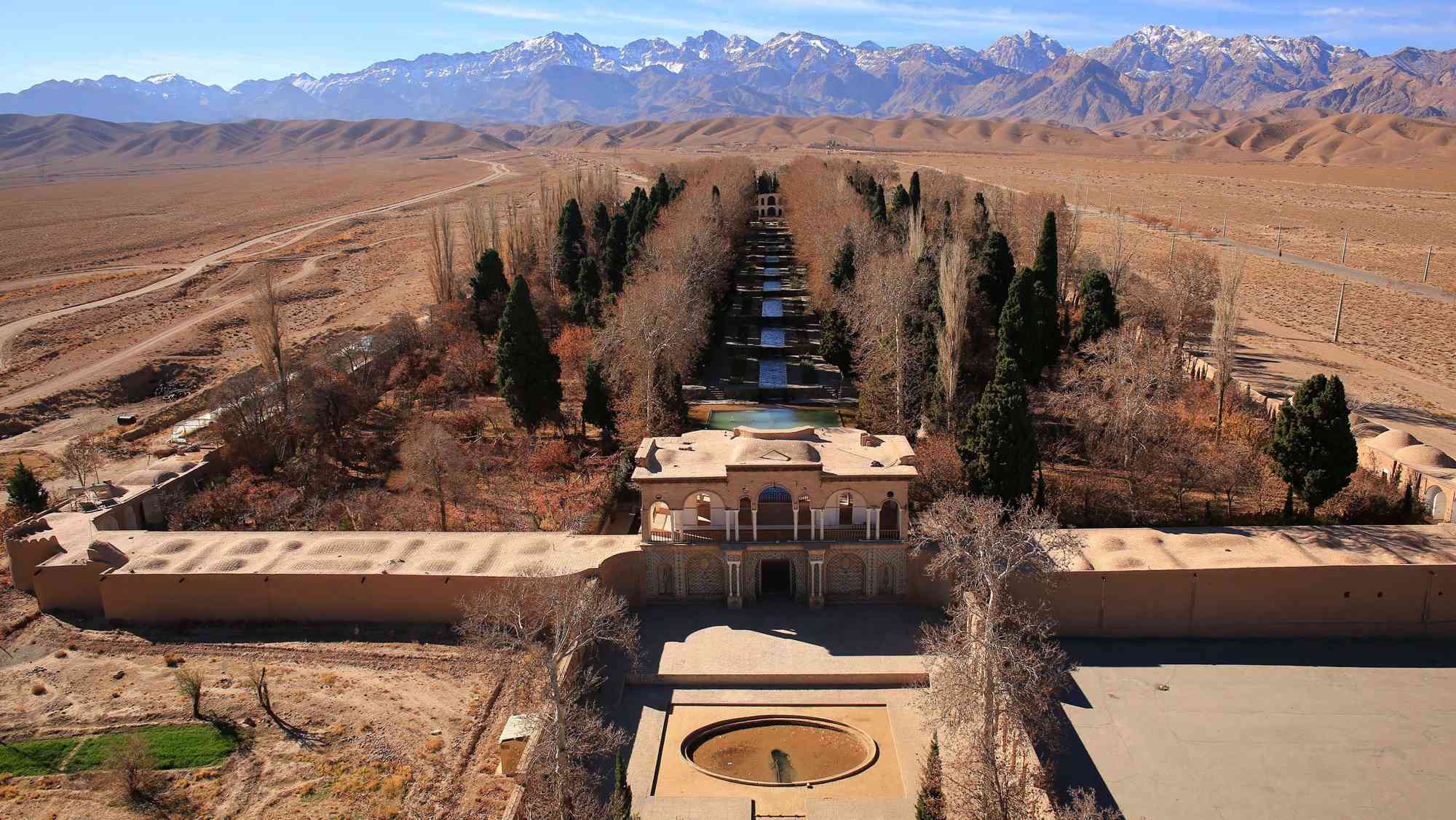

The Persian Garden

The property includes nine gardens in as many provinces. They exemplify the diversity of Persian garden designs that evolved and adapted to different climate conditions while retaining principles that have their roots in the times of Cyrus the Great, 6th century BC. Always divided into four sectors, with water playing an essential role in both irrigation and ornamentation, the Persian garden was conceived to symbolize Eden and the four Zoroastrian elements of sky, earth, water, and plants. These gardens, dating back to different periods since the 6th century BC, also feature buildings, pavilions, walls, and sophisticated irrigation systems. They have influenced the art of garden design in India and Spain.

The Persian Garden consists of a collection of nine gardens selected from various regions of Iran, which tangibly represent the diverse forms that this type of designed garden has assumed over the centuries and in different climatic conditions. They reflect the flexibility of the Chahar Bagh, or originating principle, of the Persian Garden, which has persisted unchanged over more than two millennia since its first mature expression was found in the garden of Cyrus the Great’s Palatial complex in Pasargadae. Natural elements combine with artificial components in the Persian Garden to create a unique artistic achievement that reflects the ideals of art, philosophical, symbolic, and religious concepts. The Persian Garden materializes the concept of Eden or Paradise on Earth.

The perfect design of the Persian Garden, along with its ability to respond to extreme climatic conditions, is the result of an inspired and intelligent application of different fields of knowledge, i.e., technology, water management and engineering, architecture, botany, and agriculture. The notion of the Persian Garden permeates Iranian life and its artistic expressions: references to the garden may be found in literature, poetry, music, calligraphy, and carpet design. These, in turn, have also inspired the arrangement of the gardens. The attributes that carry Outstanding Universal Value are the layout of the garden expressed by the specific adaptation of the Chahar Bagh within each component and articulated in the charts or plant/flower beds; the water supply, management, and circulation systems from the source to the garden, including all technological and decorative elements that permit the use of water for functional and aesthetic exigencies; the arrangement of trees and plants within the garden that contributes to its characterization and specific micro-climate; the architectural components, including the buildings but not limited to these, that integrate the use of the terrain and vegetation to create unique manmade environments; the association with other forms of art that, in a mutual interchange, have been influenced by the Persian Garden and have, in turn, contributed to certain visual features and sound effects in the gardens.

The Persian Qanat

Throughout the arid regions of Iran, agricultural and permanent settlements are supported by the ancient qanat system of tapping alluvial aquifers at the heads of valleys and conducting the water along underground tunnels by gravity, often over many kilometers. The eleven qanats representing this system include rest areas for workers, water reservoirs, and watermills. The traditional communal management system still in place allows equitable and sustainable water sharing and distribution. The qanats provide exceptional testimony to cultural traditions and civilizations in desert areas with an arid climate.

Throughout the arid regions of Iran, agricultural and permanent settlements are supported by the ancient qanat system of tapping alluvial aquifers at the heads of valleys and conducting the water along underground tunnels by gravity, often over many kilometers.

Each qanat comprises an almost horizontal tunnel collecting water from an underground water source, usually an alluvial fan, into which a mother well is sunk to the appropriate level of the aquifer. Well, shafts are sunk at regular intervals along the tunnel route to enable the removal of spoil and allow ventilation. These appear as craters from above, following the line of the qanat from water source to agricultural settlement. The water is transported along underground tunnels, so-called koshkan, using gravity due to the gentle slope of the tunnel to the exit (Mazhar), from where it is distributed by channels to the agricultural land of the shareholders.

Trans-Iranian Railway

The Trans-Iranian Railway connects the Caspian Sea in the northeast with the Persian Gulf in the southwest, crossing two mountain ranges and rivers, highlands, forests and plains, and four different climatic areas. Started in 1927 and completed in 1938, the 1,394-kilometer-long railway was designed and executed in a successful collaboration between the Iranian government and 43 construction contractors from many countries. The railway is notable for its scale and the engineering work it requires to overcome steep routes and other difficulties. Its construction involved extensive mountain cutting in some areas, while the rugged terrain in others dictated the construction of 174 large bridges, 186 minor bridges, and 224 tunnels, including 11 spiral tunnels. Unlike most early railway projects, the construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway was funded by national taxes to avoid foreign investment and control.

Hyrcanian Forests

Hyrcanian forests form a unique forested massif that stretches 850 km along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea. The history of these broad-leaved forests dates back 25 to 50 million years when they covered most of this Northern Temperate region. These ancient forest areas retreated during the Quaternary glaciations and expanded again as the climate became milder. Their floristic biodiversity is remarkable: 44% of the vascular plants known in Iran are found in the Hyrcanian region, which only covers 7% of the country. To date, 180 species of birds typical of broad-leaved temperate forests and 58 mammal species have been recorded, including the iconic Persian Leopard (Panthera pardus tulliana).

The Hyrcanian Forests form a green forest arc, separated from the Caucasus to the west and semi-desert areas to the east: a unique forested massif that extends from south-eastern Azerbaijan eastwards to the Golestan Province in Iran. The Hyrcanian Forests World Heritage property is in Iran, within the Caspian Hyrcanian mixed forests ecoregion. It stretches 850 km along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea and covers around 7 % of the remaining Hyrcanian forests in Iran.

The property is a serial site with 15 parts shared across three Provinces (Gilan, Mazandaran, and Golestan) and represents examples of the various stages and features of Hyrcanian forest ecosystems. Most of the ecological characteristics which characterize the Caspian Hyrcanian mixed forests are described in the property. A considerable part of the property is in inaccessible steep terrain. The property contains exceptional and ancient broad-leaved forests, which were formerly much more extensive; however, they retreated during periods of glaciation and later expanded under milder climatic conditions. Due to this isolation, the property hosts many relicts, endangered, and regionally and locally endemic species of flora, contributing to the high ecological value of the property and the Hyrcanian region in general.

Lut Desert – Kerman and Sistan and Baluchestan Provinces

The Lut Desert, or Dasht-e-Lut, is located in the country’s southeast. Strong winds sweep this arid subtropical area between June and October, which transport sediment and cause aeolian erosion on a colossal scale. Consequently, the site presents some of the most spectacular examples of aeolian yardang landforms (massive corrugated ridges). It also contains extensive stony deserts and dune fields. The property represents an exceptional example of ongoing geological processes.